The Oscar 100: #40-36

This post marks Part 13 of the 20-part series The Oscar 100. Join me as I reflect on the 100 greatest Oscar-nominated performances and what made them so richly deserving of recognition.

40. Ellen Burstyn in Requiem for a Dream (2000)

Her competition...

Joan Allen, The Contender

Juliette Binoche, Chocolat

Laura Linney, You Can Count on Me

Julia Roberts, Erin Brockovich (WINNER)

Burstyn portrays Sara Goldfarb, a lonely Brighton Beach widow who spends the bulk of her uneventful days consumed by television. Infatuated with a particular self-help program, she is ecstatic upon receiving a letter in the mail inviting her to attend a taping of the show. Too heavy to fit into her favorite red dress, Sara becomes hellbent on losing weight, ultimately embarking on a dangerous crash course involving addictive diet pills. As Sara becomes hooked on the drugs, she is overcome by terrifying hallucinations. This performance marked Burstyn's sixth (and to date, final) Oscar nomination.

100 or so years from now (hopefully longer, if scientists are able to invent the Death Becomes Her potion in time), when I hang my hat up as a moviegoer and take a moment to reflect on the greatest monologues ever delivered on the screen, there is scant doubt Burstyn's in Requiem for a Dream will tower over all others.

This isn't to say Burstyn and her glorious monologue are the lone reasons to sit through Darren Aronofsky's spellbinding motion picture. It's among the most disturbing and despairing films ever produced, a master class in filmmaking from a director somehow on only his second feature film. Jared Leto makes for an enthralling lead (actually much better here than in Dallas Buyers Club, which earned him the Oscar) and he's splendidly supported by Jennifer Connelly and yes, Marlon Wayans, in an affecting turn a far cry from the likes of Little Man and White Chicks.

Gripping as the rest of the proceedings are, however, Burstyn's Sara is the heart and soul of Requiem for a Dream. Her journey down the path of self-destruction is absolutely devastating as Sara's mundane existence, suddenly jolted by dreams of appearing on national television, is turned upside down, the amphetamine-induced psychosis transforming her little apartment into a house of horrors. Burstyn is all too convincing as Sara descends into madness, ultimately escaping home, only to stumble her way through the streets, where she is later picked up and committed into a psychiatric ward.

It is earlier in the film, however, a bit before the drugs completely consume Sara, that Burstyn gets the Oscar scene to top all Oscar scenes.

Sara's beloved son Harry (Leto) has stopped by to tell mom he's ordered her a brand new television set. Harry recognizes the effects the amphetamines are already having on Sara - the chattering of her teeth, the sky-high energy she suddenly has - and pleads with her to stop. For Sara, however, the side effects seem worth the effort. In a heartbreaking monologue, she reveals to Harry how her friends now like her more with this bubbly personality - and she hopes millions of people will soon share in their sentiment. Suddenly, there's now a reason to get up in the morning. She may be lonely, she may be old, she may have nobody to take care of anymore...but at least Sara has that dream of wearing the red dress on TV.

With these three minutes, Burstyn completely stops the show, so much so that even over the nightmarish lunacy of the proceedings to follow, it is all but impossible to get Sara's words out of your head. Requiem for a Dream may be most remembered for its striking visual style but Aronofsky's screenplay - and his actors' exquisite delivery of it - is not to be underestimated.

When, during the 2000 awards season, Burstyn labeled her turn as Sara as the role of her career, such wasn't hyperbole, even with the rest of her immaculate filmography considered. Yet, inexplicably, Burstyn hadn't a prayer on Oscar night. The cake was baked for Roberts to grace the stage for her much-celebrated star turn as Erin Brockovich. Remarkably, Burstyn failed to ever garner a major critics' award during the season's precursors, as Roberts and Linney picked up a plethora of prizes.

Such recognition for Roberts and Linney is hardly to be knocked - both are terrific, as is Allen (per usual) - but come on, none of these performances, great as they are, holds a candle to what Burstyn pulls off in this picture. It's gut-wrenching, career-best work from one of the 10 or so finest actresses to ever grace the big screen.

39. Katharine Hepburn in Long Day's Journey Into Night (1962)

Her competition...

Anne Bancroft, The Miracle Worker (WINNER)

Bette Davis, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?

Geraldine Page, Sweet Bird of Youth

Lee Remick, Days of Wine and Roses

Hepburn portrays Mary Tyrone, matriarch of a Connecticut family in deep decline. Mary's sickly son Edmund (Dean Stockwell) returns home to find his mother further descending into her morphine addiction. Edmund's alcoholic father, the retired actor James (Ralph Richardson), isn't in much better shape, nor is his volatile brother Jamie (Jason Robards). As Edmund and Jamie quarrel over how to help their mother, Mary agonizes over Edmund's dwindling health. This performance marked Hepburn's ninth Oscar nomination.

In May 1962, for the sole occasion over her storied career on the big screen, Hepburn earned the Best Actress prize at the Cannes Film Festival for her electrifying turn as Mary Tyrone in Sidney Lumet's film adaptation of Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey into Night. Her trio of leading men shared honors in Best Actor and, odds are, the picture didn't finish terribly far behind Anselmo Duarte's The Given Word for the Palme d'Or.

Tragically, the picture wasn't the least bit commercially successful upon its U.S. release. Receipts were so anemic, the eminent producer Joseph E. Levine, who picked up distribution rights after its smashing success at Cannes, vowed to never again invest in an O'Neill adaptation. Hepburn, nonetheless, would earn her obligatory Best Actress Oscar nomination, not that she was deemed to have a prayer against the likes of Bancroft, Davis and Page, all headlining films that were big hits.

This middling reception for Long Day's Journey - and the difficulty film buffs have faced in recent years in accessing Lumet's picture - just breaks my heart, as the film sports one of Hepburn's very best and most surprising performances. Her leading men are too in prime, Oscar-caliber form and Lumet's direction is among his finest work of the '60s. To me, this is the definitive adaptation of O'Neill's play, so what a damn shame hardly anybody has seen it.

Hepburn is shot much like Elizabeth Taylor would be in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? a few years down the road, with extreme close-ups that accentuate her emotions and make the performance all the more startling. Indeed, much like the later Mike Nichols picture, Lumet keeps the proceedings here from ever feeling claustrophobic by positioning the camera in a dizzying way that keeps the action exciting and intrusive. For a nearly three-hour film, Long Day's Journey flies by in remarkable fashion.

The confidence and cleverness of Hepburn's past performances makes her anxious, fragile portrayal of Mary all the more shocking. Hepburn astutely utilizes her essential tremor, which had become more pronounced since her last picture (Suddenly, Last Summer, three years earlier), to paint Mary as an antsy and uncontrollable woman - the more emotional her Mary becomes, the more her head shakes and body quivers. The sight of Hepburn rolling around on the floor, a drugged-up nervous wreck, barely able to function anymore, is the truly horrific to behold. And she absolutely slays in her final monologue that closes out the film.

Long Day's Journey might not quite be the best of all Hepburn performances - there are more to come in this series - but it sure comes close. This is a masterful and unconventional turn from an actress who never before (or after) played such a frenzied, deteriorating creature.

38. Julianne Moore in Far from Heaven (2002)

Her competition...

Salma Hayek, Frida

Nicole Kidman, The Hours (WINNER)

Diane Lane, Unfaithful

Renee Zellweger, Chicago

Moore portrays Cathy Whitaker, the quintessential 1950s suburban housewife. Life is seemingly peachy keen for Cathy - she has adorable kids, a successful, handsome husband and a beautiful home in the tidiest of order. Then, one evening, Cathy walks in on hubby Frank (Dennis Quaid) kissing another man in his office. Their relationship becomes a strained one, as Frank hits the bottle and, to no avail, battles his homosexuality. Cathy's life is all the more rattled by the neighborhood's response to her newfound friendship with Raymond (Dennis Haysbert), an African-American and the son of the Whitakers' late gardener. This performance marked Moore's third/fourth Oscar nomination (she was also nominated this year for The Hours).

2002 was the very first awards season I closely followed - that is, intently enough where I was keeping track of all of the precursor awards and making predictions for both nominations and winners. For some time that year, I was over the moon in delight over the positive response to Moore, who picked up a number of major critics' awards and, for all too brief a period, looked like the front-runner to grab the Best Actress Oscar.

Then, tragically, both Moore and Far from Heaven kind of petered out. Reviews may have been unanimously glowing but the picture's box office returns were much more modest. It didn't earn a Best Picture nomination at the Golden Globes, nor did the Directors Guild or Producers Guild bite. By Oscar night, the race for Best Actress had evolved from Moore sitting on top as a soft front-runner to a barn burner showdown between Kidman and Zellweger, both gracing Best Picture nominees. With pundits ranting and raving over who of the two would prevail, Moore, Hayek and Lane all fell to the sidelines.

What a shame such came to fruition, as neither Kidman nor Zellweger comes remotely close to achieving the greatness of Moore in Far from Heaven (only Lane gives a performance that could also be labeled awe-inspiring).

Like Dorothy Malone in Written on the Wind and Juanita Moore in Imitation of Life (director Todd Haynes was of course visually inspired by Douglas Sirk), Moore's performance is surrounded by glorious Technicolor imagery but never is her turn drowned out in any way by the beauty around her. In a way, Moore's effort is even more remarkable an accomplishment than Malone's, for instance, the latter of who stood out by delivering a fierce, larger-than-life scene-stealer of a performance. Moore manages to own the spotlight with a sumptuously subdued and understated portrayal.

That Moore's performance is so restrained makes it all the more heartbreaking when Cathy is punched in the gut, first by her husband, then by her prejudiced community and finally by Raymond, who shatters his dear friend in the film's unforgettable conclusion - one of the most painful scenes ever captured on film.

Cathy's evolution throughout the film is riveting, as she goes from perfectly pleasant, unworldly Connecticut housewife to a confused, wounded woman, at last opening her eyes to the realities of the world outside the idyllic masquerade of the suburbia around her.

Moore's scenes opposite Quaid (who is incredible and surely deserved an Oscar nom too) are equal parts convincing and agonizing and her rapport with Haysbert (also brilliant) is immensely soulful and affecting. Their union appears doomed from the get-go but it's impossible to not still get deeply, emotionally involved with the pair. With a single, simple line ("you're so beautiful"), Moore is able to convey so much - Cathy's loneliness, regrets and dreams of what could be under different circumstances.

Far from Heaven, spearheaded by Moore's exquisite performance, is a tear-jerker of the first degree, the sort of devastating melodrama that comes around all too rarely. I could watch it over and over again, even if it never fails to destroy me.

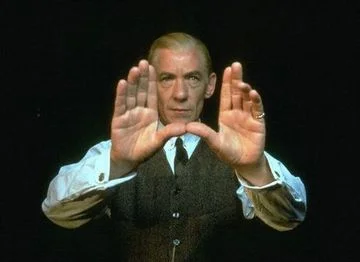

37. Ian McKellen in Gods and Monsters (1998)

His competition...

Roberto Benigni, Life Is Beautiful (WINNER)

Tom Hanks, Saving Private Ryan

Nick Nolte, Affliction

Edward Norton, American History X

McKellen portrays James Whale, once a renowned Hollywood filmmaker in the 1930s but by the 1950s, in increasingly fragile health, spending retirement alongside his disparaging but loyal housekeeper Hanna (Lynn Redgrave). The openly gay Whale has had no shortage of young male lovers in and out of his home but the arrival of new gardener Clayton Boone (Brendan Fraser) presents the director with a more intriguing and meaningful conquest. This performance marked McKellen's first Oscar nomination.

Oh, how it pains me to revisit this category.

In 1998, voters rightfully recognized the sublime likes of McKellen, Nolte and Norton - all at their career-best - plus Hanks, also in fine form, for Best Actor nominations. Joining them could have been Jim Carrey in The Truman Show or John Travolta in Primary Colors (both sensational), among others. Instead, the Miramax machine won out and Roberto Benigni, whose mawkish Life Is Beautiful came on strong that awards season, nabbed that remaining slot.

With Benigni's turn the one crowd-pleaser against a quartet of heavy, tragic turns, plus the industry inexplicably eating up both his picture and enthusiastic acceptance speeches, it would be him, not McKellen, Nolte or Norton (all favorites of the critics), emerging triumphant. All three of these brilliant actors remain Oscar-less to this day.

Earlier, I lavished praise upon Nolte's stirring work in Affliction but my ultimate preference in the category is McKellen and his vivid portrayal of the legendary Frankenstein filmmaker.

McKellen's Whale may be an exhausted sight, on the verge of knocking on death's door, but he exudes a spirit that palpably suggests the magnetic man that once was. At this point, Whale spends his days anguished by memories of the past, relying on Hanna, who isn't shy in her disapproval of her employer's sex life, to keep things in order and get him through the day. McKellen and Redgrave have a ball in their scenes together, two old pros going to town on Bill Condon's terrific, Oscar winning screenplay.

Though Fraser may not be an actor at quite the same level as McKellen and Redgrave, he's an ideal, inspired fit for the alluring role of Clayton Boone, at times even suggesting Montgomery Clift. With Whale losing his grip on reality and despondent over both his looks and health fading away, the filmmaker finds great solace in his new friendship with Boone, a relationship at last not exclusively sexual in nature, even if there is scant doubt about Whale's attraction to the dashing former marine.

The picture and McKellen's performance become overwhelming as the film reaches its conclusion. Whale's appearance at a party thrown by fellow filmmaker George Cukor and attended by The Bride of Frankenstein's Boris Karloff and Elsa Lanchester only worsens his misery. At his most despondent ever, Whale decides to make sexual advances on Boone, hoping the young man will perhaps retaliate and kill him. This play isn't a success - instead of bloodthirsty outrage, Boone largely feels pity for his sad, hopeless friend. Whale is left to suffer with no light on the horizon.

When McKellen earned his nomination, he stood to emerge the first openly gay performer to take home the Best Actor Oscar (John Gielgud marked the first of any category, in Best Supporting Actor in 1981). The recognition for his performance and the film overall felt downright revolutionary just two decades ago. While he may have fallen short, his performance has unimpeachably stood the test of time better than the Academy's preference and there is scant doubt he'll someday make a return to Oscar night, perhaps even in Best Actor again (where he would still make history as the first openly gay winner).

36. Roy Scheider in All That Jazz (1979)

His competition...

Dustin Hoffman, Kramer vs. Kramer (WINNER)

Jack Lemmon, The China Syndrome

Al Pacino, ...And Justice for All

Peter Sellers, Being There

Scheider portrays Joe Gideon, a choreographer and director on the verge of a nervous breakdown. The ultimate workaholic, Gideon relies on pills, cigarettes and sex to get him through an especially exhausting time in his life, as he both stages his latest Broadway musical and edits the motion picture he recently filmed. The physical and emotional stress increasingly takes a toll on the perfectionist who, to his great chagrin, ends up admitted into a hospital, where he becomes consumed with memories from the past, staged in his mind as splashy musical numbers. This performance marked Scheider's second and final Oscar nomination.

From the picture's spellbinding opening, set to George Benson's "On Broadway," to the final, tragic shot of Joe Gideon's corpse zipped into a body bag, Bob Fosse's All That Jazz is the most riveting of entertainment, a career-best effort from a filmmaker who never made a bad picture.

Front and center, surrounding by all of Fosse's dizzying pyrotechnics and Alan Heim's frantic, Oscar winning film editing is leading man Scheider, taking on a role worthy of his sky-high talents. Sure, Scheider worked wonders before with the likes of The French Connection, Jaws and Marathon Man but none of those parts offered anywhere near the meat to chew on as Fosse (and co-writer Robert Alan Aurthur) served up for the actor in All That Jazz.

Scheider, who generally sported an amiable everyman quality in his previous turns, is downright electrifying as Gideon, a semi-autobiographical version of the picture's director. With another, less convincing actor, Gideon may have been left overshadowed by all of the madness around the character but Scheider never allows himself to be upstaged. It's among the zestiest, most energetic performances to ever grace the big screen.

Gideon may be a difficult figure to love - he takes recklessness to new levels and has negligible empathy for anyone around him - but his journey sure is a riveting one, as he overworks himself into the hospital and manages to only worsen his condition while admitted, suffering not one but two heart attacks.

As mortality rears its ugly head and his film goes down the toilet, Gideon's antics only intensify and he becomes preoccupied by one dream sequence after another, each one more maddening than the last. Yet, despite Gideon's bad behavior, it's hard not to feel punched in the gut by his demise - his brilliance, in the end, manages to overshadow his cruelty and narcissism.

From beginning to end, Scheider is never anything less than perfection. Yet, on Oscar night, he didn't really have much of a prayer.

All That Jazz unexpectedly earned a boatload of nominations, tying Kramer vs. Kramer for most recognition (nine nominations), and ended up scoring four wins but Scheider was never seen in real contention for the Best Actor win. Hoffman steamrolled that awards season, with only the Oscar-less Sellers seen as a threat. When Being There failed to earn nominations in Best Picture, Best Director or Best Original Screenplay, however, Sellers' hopes looked all the dimmer. Ultimately, only Hoffman and Lemmon would even show up at the ceremony.

I can't much knock Hoffman's victory - he's fantastic, as is Kramer vs. Kramer - but better is Scheider, turning in one of the fiercest performances ever recognized in Best Actor.

The Oscar 100 (thus far)...

36. Roy Scheider, All That Jazz

37. Ian McKellen, Gods and Monsters

38. Julianne Moore, Far from Heaven

39. Katharine Hepburn, Long Day's Journey Into Night

40. Ellen Burstyn, Requiem for a Dream

41. Whoopi Goldberg, The Color Purple

42. Barbra Streisand, Funny Girl

43. Marlon Brando, On the Waterfront

44. William Holden, Sunset Boulevard

45. Robert Duvall, The Great Santini

46. Anthony Hopkins, Nixon

47. Joan Allen, Nixon

48. Nick Nolte, Affliction

49. James Coburn, Affliction

50. Ingrid Bergman, Autumn Sonata

51. Meryl Streep, The Bridges of Madison County

52. Patricia Neal, Hud

53. Susan Tyrrell, Fat City

54. Teri Garr, Tootsie

55. Kim Stanley, Seance on a Wet Afternoon

56. Thelma Ritter, Pickup on South Street

57. Geraldine Page, Interiors

58. Dorothy Malone, Written on the Wind

59. Olivia de Havilland, The Heiress

60. Brenda Blethyn, Secrets & Lies

61. Faye Dunaway, Network

62. Jane Darwell, The Grapes of Wrath

63. Vivien Leigh, A Streetcar Named Desire

64. Shirley MacLaine, Terms of Endearment

65. Angela Lansbury, The Manchurian Candidate

66. Natalie Portman, Jackie

67. Martin Landau, Ed Wood

68. Ellen Burstyn, The Last Picture Show

69. Cloris Leachman, The Last Picture Show

70. Jane Alexander, Testament

71. Jean Hagen, Singin' in the Rain

72. Barbara Stanwyck, Stella Dallas

73. Sissy Spacek, Carrie

74. Piper Laurie, Carrie

75. Agnes Moorehead, The Magnificent Ambersons

76. Elizabeth Taylor, Suddenly, Last Summer

77. Fredric March, The Best Years of Our Lives

78. Meryl Streep, Sophie's Choice

79. Bette Davis, All About Eve

80. Dustin Hoffman, Tootsie

81. Jason Miller, The Exorcist

82. Michael Caine, Hannah and Her Sisters

83. Judith Anderson, Rebecca

84. Michael O'Keefe, The Great Santini

85. Robert De Niro, The Deer Hunter

86. William Holden, Network

87. George Sanders, All About Eve

88. Jill Clayburgh, An Unmarried Woman

89. Sally Kirkland, Anna

90. Morgan Freeman, The Shawshank Redemption

91. Maureen Stapleton, Interiors

92. Glenn Close, Dangerous Liaisons

93. John Hurt, The Elephant Man

94. James Stewart, It's a Wonderful Life

95. Gary Busey, The Buddy Holly Story

96. Kathy Bates, Primary Colors

97. Lesley Ann Warren, Victor/Victoria

98. Rosie Perez, Fearless

99. Shelley Winters, A Place in the Sun

100. Kathleen Turner, Peggy Sue Got Married

Next week - rejoice, fellow Katharine Hepburn fans! She's back, this time alongside a co-star from the same picture. Joining them are the trio of leading ladies from the '40s, '60s and '90s, including one legendary winner